Before diving into the substance of the Senate market structure debate, it is worth acknowledging that many of the industry’s concerns are not frivolous. Warnings about slowing innovation, experimentation moving offshore, and regulatory uncertainty chilling development deserve serious attention. For that reason, Brian Armstrong is right to flag those risks. The analysis that follows does not ignore these arguments or dismiss them as self-interest. It starts from the premise that those fears are real, then asks a narrower question: how lawmakers are weighing innovation against consumer protection as crypto moves from a niche system for early adopters toward mainstream financial infrastructure.

Even the most crypto-native builders ultimately want systems that can scale without constant trust failures. But that requires clarity about where autonomy ends and responsibility begins.

Why One Tweet Was Enough to Stall a Senate Bill

The Senate Banking Committee’s decision to cancel the scheduled markup of its crypto market structure bill was unusual, but not mysterious. The immediate trigger was a public withdrawal of support by Brian Armstrong, CEO of Coinbase, who argued that the draft was worse than the regulatory status quo and not something the industry could accept.

The public debate framed this moment a clash between innovation and regulation. Some even presented it as proof that lawmakers are hostile to crypto itself. That framing misses what is actually at stake. The bill was not derailed because it outlawed digital assets or shut down decentralized finance. What derailed it were the uncomfortable answers to a simpler question: who bears risk when crypto scales beyond early adopters?

Crypto’s existence is no longer in doubt. What remains unresolved is how crypto fits into a financial system built around consumer protections, institutional responsibility, and political accountability when things go wrong. The market structure bill was an attempt to answer that question. Armstrong’s reaction helps explain why that answer is so contentious.

Taking Armstrong’s Objections Seriously — Not Symbolically

Armstrong’s statement listed four core objections: a supposed ban on tokenized equities, restrictions on DeFi and privacy, erosion of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission’s authority in favor of the Securities and Exchange Commission, and amendments that would eliminate stablecoin rewards.

These complaints are often dismissed as industry self-interest. That would be too easy; and analytically lazy. Each objection maps directly onto how large crypto exchanges operate, how they grow, and how they compete with traditional financial institutions. None of them are random.

What matters is not whether one agrees with Armstrong’s conclusions, but whether the bill genuinely alters the structure of crypto markets in ways that affect consumers, intermediaries, and regulators differently. When stripped of rhetoric, his objections point to a draft that reduces ambiguity, narrows gray zones, and limits the ability to scale financial products without assuming corresponding obligations.

That is precisely why this market structure bill mattered.

>>> Read more: Crypto Coalition Presses Senate for DeFi Developer Protections

Crypto’s Own Framing: “We Compete With Banks”

For years, large crypto firms have argued that they compete directly with banks. They describe stablecoins as money. Exchanges become financial hubs. DeFi is presented as alternative market infrastructure. This framing has been central to crypto’s pitch to policymakers and the public alike.

But competition is not just about features or technology. It is about serving the same customers, performing the same economic functions, and meeting similar expectations. Once crypto positions itself as an alternative to mainstream financial services, it no longer operates solely in a niche of informed risk-takers.

This is where the regulatory conversation shifts. Competing with banks does not merely invite lighter rules in the name of innovation. It invites scrutiny over whether consumers are being offered comparable protections or whether risk is being quietly transferred to crypto users under the banner of choice.

The Senate draft takes that framing seriously. Armstrong’s objections, in turn, reveal how costly that seriousness can be for existing business models.

In that sense, consumer protection is not an external constraint on crypto innovation, but a prerequisite for trust at scale. When that trust is missing competition with incumbent systems never moves beyond niche adoption.

Two User Groups, One Regulatory Reality

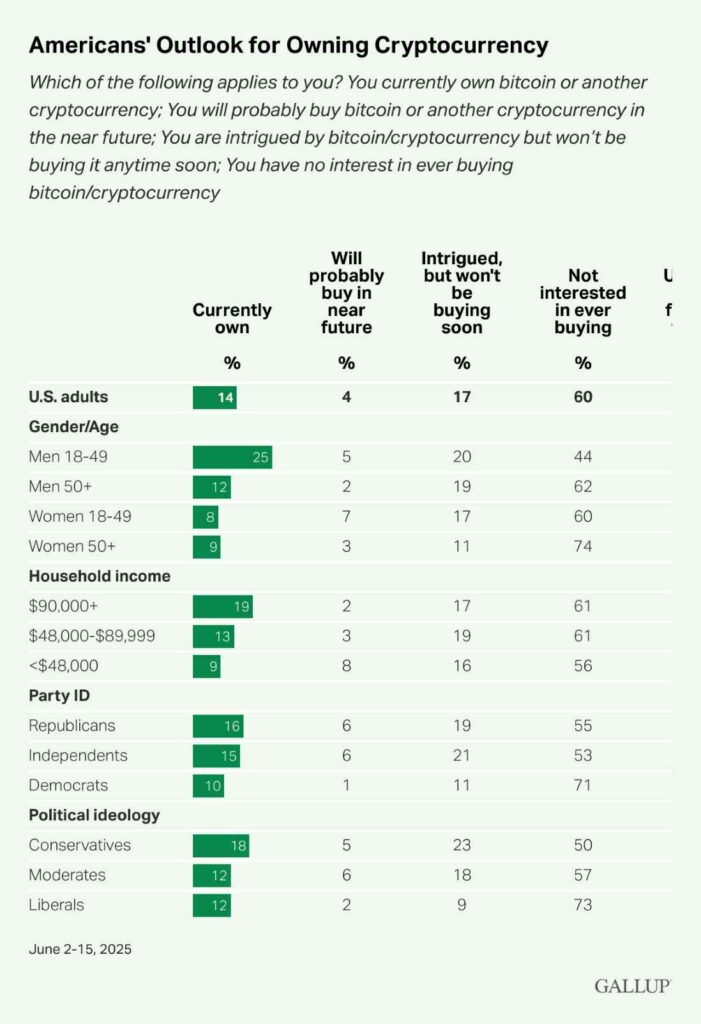

Much of the tension in crypto regulation stems from the fact that there are effectively two audiences using the same systems.

The first consists of crypto-native users. They understand volatility, custody risk, smart-contract failure, and the absence of guarantees. They are comfortable trading protection for autonomy and yield. Losses, while painful, are understood as part of participation.

The second group is far larger and less visible in policy debates: mainstream users. These users interact with crypto through apps and interfaces that look and feel like traditional finance. They see balances, rewards, and familiar terminology. They do not audit smart contracts, parse governance structures, or assume that a failed intermediary leaves them without recourse.

Regulation written exclusively for the first group fails the second. And once mass adoption becomes the goal, that failure becomes political.

The Senators drafted the market structure bill with this reality in mind. It assumes that most users will not behave like early crypto adopters and therefore, consumer protections cannot depend on user sophistication.

We Don’t Have to Guess What Failure Looks Like

This debate is not happening in a vacuum. Over the past several years, multiple centralized crypto exchanges and lending platforms have failed. In those failures, consumers did not merely suffer price volatility. They lost access to funds, became unsecured creditors, and entered bankruptcy processes that dragged on for years.

These outcomes were not edge cases. They were systemic consequences of operating financial intermediaries without resolution regimes, capital requirements, or fiduciary obligations comparable to those in traditional finance.

Failures occur in every financial system. What distinguishes one system from another is not whether things break, but who absorbs the damage when they do. In banking, losses are buffered through layers of regulation that protect depositors and contain contagion. In crypto, losses have often flowed directly to users.

The Senate draft reflects that history. It is less a reaction to theoretical risk than an attempt to respond to harm that has already occurred. Ultimately, regulators and lawmakers had to answer for that harm.

From this perspective, consumer protection is less about preventing failure and more about ensuring that failure does not destroy confidence in the system as a whole.

DeFi and Developer Liability: What the Bill Actually Says

One of the loudest objections to the Senate draft is the claim that it would make developers legally responsible for how decentralized tools are used. This argument has traveled fast in crypto circles, often framed as an attack on open-source software itself. But when read carefully, the text does not support that interpretation.

The draft does not regulate the act of writing code. It does not impose liability simply for publishing a smart contract, contributing to a protocol, or releasing open-source software. There is no provision that equates authorship with financial intermediation.

What the bill does target is control and economic function. Obligations arise when an actor exercises discretion over transactions, operates an access layer, maintains control over user assets, earns fees from facilitating trades, or otherwise functions as an intermediary between users and markets.

Much of what is described as “DeFi” today is experienced through interfaces, frontends, governance structures, and managed access points that behave like services. The bill focuses on those layers, not on the underlying code.

It is not criminalizing the development. It is the collapse of a long-standing gray zone that allowed economic intermediation without responsibility. This distinction will not eliminate uncertainty for developers, but it narrows it by tying regulatory obligations to control and intermediation rather than to the act of writing or publishing code.

By clarifying where responsibility actually begins, the bill arguably gives builders more room to innovate outside those boundaries, rather than forcing all activity to exist in perpetual legal ambiguity.

Tokenized Equities: Parity, Not Prohibition

Another flashpoint in Armstrong’s critique is the claim that the Senate draft imposes a “de facto ban” on tokenized equities.

The bill does not prohibit tokenized equities. It insists that if an instrument represents equity-like rights, it remains subject to securities law, regardless of the technology used to issue or transfer it. Tokenization may change settlement mechanics, but it does not change the economic nature of ownership.

This is a deliberate market-structure choice. Allowing tokenized equities to trade under a lighter regime would recreate equity markets with fewer safeguards and weaker disclosure. The Senate draft blocks that path.

Calling this a ban only makes sense if one assumes innovation should automatically dilute investor protections. The bill rejects that assumption.

SEC vs. CFTC: Closing the Arbitrage Window

The dispute over regulatory jurisdiction is often framed as innovation versus enforcement. In reality, it is about who sets the compliance baseline for crypto markets.

The Senate draft does not eliminate the role of the CFTC, nor does it subordinate it to the SEC. What it does do is narrow the ability to move assets and activities between regimes based on convenience.

Jurisdiction is determined more tightly by economic substance rather than labeling. For exchanges, this reduces regulatory flexibility. For consumers, it reduces confusion and surprise.

This is a governance decision aimed at clarity, not an attempt to suppress innovation.

>>> Read more: SEC Token Taxonomy: Atkins Says Most Tokens Aren’t Securities

Stablecoin Rewards: Where the Bill Draws a Hard Line

Of all the objections raised, this is where the Senate draft is most explicit; and where the conflict becomes unavoidable.

The bill draws a clear line between payment instruments and deposit-like products. Stablecoins may be used for transfers and settlement. What they may not do is pay yield simply for being held.

Yield implies interest. Interest implies safety. And safety implies safeguards.

By prohibiting yield on passive stablecoin balances, the bill prevents stablecoins from quietly functioning as shadow deposits without deposit-level protections. For exchanges, this closes a powerful growth lever. For consumers, it removes a source of silent risk transfer.

This distinction does not remove user choice; it makes the trade-offs legible, separating payment utility from risk-bearing investment in a way that supports informed adoption rather than accidental exposure.

This is the point where business models collide with regulatory logic and where support ultimately collapsed.

Lobbying, Power, and the “Banks Wrote the Bill” Claim

Critics of the Senate’s market structure draft argue that banking interests helped shape the bill in ways that tilt the competitive landscape in favor of incumbent institutions. In this view, the issue is not that banks received explicit carve-outs, but that the bill would force crypto-native firms, fintechs, and other non-bank intermediaries to operate under bank-like constraints. Those constraints raise costs, slow experimentation, and make it harder for alternative models to compete on distinct terms.

That critique is directionally correct. The bill does narrow regulatory gray zones, raise compliance thresholds, and make balance-sheet risk without backstops harder to sustain. These changes do constrain non-bank competitors.

The disagreement lies in why those constraints exist. One interpretation is regulatory capture: banks lobbied to impose rules they already meet. Another is regulatory path dependence: lawmakers applied a consumer-protection baseline to crypto that was shaped by decades of financial crises and voter backlash to any actor performing bank-like economic functions.

The Senate draft reflects the latter logic. It does not grant banks exemptions or new privileges. Instead, it applies a single premise: intermediaries that hold customer balances and facilitate transactions at scale must absorb responsibility when things fail. Banks benefit not because the market structure bill favors them, but because they already operate within that perimeter.

That choice is not neutral in its effects. Regulatory design always produces winners and losers. Lawmakers made a policy judgment about risk and accountability, rather than attempting to insulate incumbents from competition.

From a system-design perspective, the question is not whether competition should exist, but whether competition built on lower accountability can remain stable as participation broadens.

Why the Senate Draft Looks So Different From the House Bill

The contrast with the House approach helps explain Armstrong’s reaction. The House framework emphasizes carve-outs, decentralization exemptions, and faster market expansion. The Senate draft emphasizes parity, clarity, and integration. For crypto-native firms, this shift understandably feels less like neutral integration and more like being forced into a regulatory architecture designed for incumbents.

One vision prioritizes growth. The other prioritizes compatibility with an existing financial system where consumer harm quickly becomes a public problem.

Armstrong’s withdrawal makes sense in this context. The Senate draft does not prohibit crypto, but it forces it to choose between scale with safeguards or autonomy with limits.

The Transition Is the Danger Zone

Even if crypto’s end state proves safer and more efficient, history suggests the greatest risk lies in the transition.

Financial harm concentrates when systems scale faster than protections, when users adopt products they do not fully understand, and when responsibility is diffuse. This is not unique to crypto. It is a recurring feature of financial innovation.

The Senate draft slows that transition deliberately. That friction frustrates firms built around speed and ambiguity. But from a consumer perspective, friction can be a feature, not a bug.

Innovation and accountability are not opposing forces here; together, they determine whether growth is temporary and fragile or durable and widely trusted.

What This Fight Is Really About

Armstrong did not walk away because the Senate draft bans crypto, criminalizes developers, or hands the future to banks. He walked away because the bill forces clarity. Clarity about who intermediates, who bears risk in crypto, and what protections consumers should reasonably expect.

Crypto can remain a high-risk system for informed participants. Or it can become mainstream financial infrastructure with mainstream safeguards. What it cannot easily be is both at once.

Crypto’s future may be inevitable. Ensuring that innovation scales with accountability, rather than at its expense, is the policy choice still being made.